On the easel / under construction as at 6 Feb 2019.

Click for a larger image:

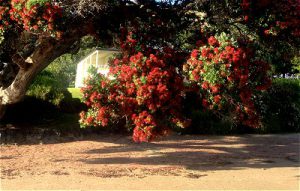

- The glorious flowering Pohutukawa tree (Metrosideros excelsa) is an icon of the New Zealand summer and is nationally included in postcards, paintings, and other “kiwiana” memorabilia. A coastal tree that flowers in bright red over the December-January holiday period, it often grows so close to the ocean that its branches and flowers overhang the water.

- New Zealand Orca are unique in their culture of hunting rays and skates in shallow water, including shorelines, harbours, estuaries, and even tidal rivers.

I haven’t actually seen an Orca passing a flowering Pohutukawa tree, but I reasoned that it must happen… I was fishing at the base of a cliff near the mouth of the Weiti River, which borders the south side of the Whangaparaoa (“Bay of Whales”) Peninsula. Partially hanging over me was a large Pohutukawa tree in flower. At my feet was a stingray feeding in the warm shallows on the incoming tide. I realised that summer stingrays coincide with summer Pohutukawa flowering. Therefore Orca must pass overhanging flowering Pohutukawa trees as they hunt stingrays in shallow water throughout the North Island, just as they do (rarely) in the Weiti River.

Examples of Pohutukawas hanging over water

Here are some examples from just a few of the bays of my home area:

Orca are “cultural” mammals

(Not culture as in music and art, but as in a body of knowledge passed through generations)

Culture is such a determining factor in the lives of Orca that some cultures don’t mix, even though they are the same species inhabiting the same areas of ocean. For example, genetic evidence suggests that “transient” mammal-hunting Orca off North America have not interbred with the “resident” coastal fish-hunting Orca for nearly a million years, although they must frequently cross paths and are fully capable of interbreeding.

Orca are the largest of the dolphins (small toothed whales). Possibly more so than other dolphins, they are “cultural” animals, meaning that the strategies and behaviours of the Orca pod are educationally (not genetically) passed on from generation to generation in an unbroken cultural chain. So if we transported a pod of Icelandic Orca to New Zealand, they would not know how to hunt stingrays. If we “cut” the cultural parent-calf educational chain of New Zealand Orca, the uneducated youth would also not know how to hunt stingrays. And if we released a captive-bred Sea World Orca in New Zealand, it also would not know how to hunt stingrays, or any other fish or mammal. By contrast, a shark is a non-cultural animal – it has a genetic blueprint on how to hunt, so after birth, it does not need to learn from a parent.

The same cultural continuity (and potential discontinuity) is evidenced in humans. In a single urbanised generation of African San (“Bushmen”) the accumulated hunter-gatherer herbal wisdom of some 180 000 years was lost, likely irretrievably, because before urbanisation they were a preliterate people and their extensive knowledge had never been thoroughly documented.

Orca culture of stingray-hunting

Globally, Orca have learned that when flipped upside down, sharks, skates, rays, and sawfish (the Elasmobranchs) go into a state of “tonic immobility”, a hypnotic, trance-like state where they barely move or respond. This peculiarity enables Orca to feed on a range of Elasmobranchs, from stingrays and small sharks all the way up to 4-metre White Sharks.

In New Zealand, their speciality is stingrays. The stingrays seem to be very aware of the Orca threat – while diving I’ve seen stingrays tucked under ledges, and strangely, inside close-fitting potholes. The potholes they choose are deep and narrow enough to block a large Orca head and jaw, but it must take some nerve to lie still while those big teeth are bared just centimetres away. It takes a lot to move them out of their safe holes. I’ve had to resort to touching them with the speargun before they take off in a flutter.

Orca typically roll upside down before approaching a stingray, grab the stingray and then immediately roll right-way-up, leaving the stingray inverted and catatonically immobile. This prevents the stingray thrashing and stabbing its barbed tail spike into the Orca (note that the tail spike is large – the legendary Steve Irwin very sadly met an early end when a stingray spiked him multiple times in the chest and heart).

Stingray hunting is risky:

- Orca roll upside down in shallow water, where a many tons of weight on a non-repairing cartilaginous Orca dorsal fin could do permanent damage.

This may explain why New Zealand Orca have the highest percentage damaged dorsal fins in the world, as noted by New Zealand’s Orca Research Trust – http://www.orcaresearch.org.

If so, male Orca with their dorsal fins of up to 1.8 metres may suffer more damage than female Orca. - The dangers of shallow-water stingray hunting are also evidenced by New Zealand Orca having the highest Orca-stranding rates in the world, as noted by the Orca Research Trust.

More info online:

Youtube Search: “NZ Orca hunting stingrays”

Note on White Shark hunting:

For many years a pair of male Orca in the south of Southern Africa have killed large Great White sharks and “surgically” removed and ate just their fat-rich livers. This predation on White Sharks is neither unique nor recent and it has been documented in multiple regions. Both electronic shark-tracking in North America and anecdotal evidence in South Africa show that White Sharks flee immediately from a site where Orca kill one of their kind, and they stay away from the area for weeks or months. In other words, White Sharks are seriously afraid of Orca.

Youtube Search: “Orcas hunt Great White Sharks in South Africa”

Very interesting article about the Orca I had no idea that there were Orca’s from the north and south in the world.I enjoyed seeing your paintings with explanations.

Thanks Margaret. I guess we know Orcas via global media, and the media has always been dominated by countries in the Northern Hemisphere. Canadian and Icelandic Orca for example, are a tiny proportion of the global population, as are our 200-odd Orca in NZ. Apparently the global population is about 100 000, and of those, about 70 000 are resident in Antarctica! So if we look just at the numbers, they are primarily an Antarctic species with a thin scattering around the globe. But that scattering is significant because it is FULLY global – I read somewhere that they are the most globally widespread animal after humans.